In Progressive Era Chicago, boys had the opportunity to learn and master trades such as carpentry, construction drawing, electric shop, and mechanics so they could become the next generation of tradesmen. But while boys were the focus of this educational revolution, girls also strove to learn vocational trades to help them thrive in the industrial workforce.

“’A Superior Kind of Working Woman’: The Contested Meaning of Vocational Education for Girls in Progressive Era Chicago,” published in The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, follows the history of girls’ vocational schools in Chicago and the different courses and vocational trades they were taught.

Dr. Ruby Oram, Assistant Professor of Practice in the Department of History, shares how much work was required to create vocational high school programs for girls. Her historical analysis also shows tension between progressive women focused on training girls for an industrial career and traditional middle-class reformers who still advocated for preparing girls for homemaking and motherhood.

Jane Addams, Mary Morton Kehew, Agnes Nestor, and other members of the National Society for the Promotion of Industrial Education (NSPIE) and the National Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) advocated for including women in vocational training and apprenticeships. They faced resistance from Chicago school officials, but enough pressure finally grew to open a public vocational school for girls in 1911: the Lucy Flower Technical High School for Girls.

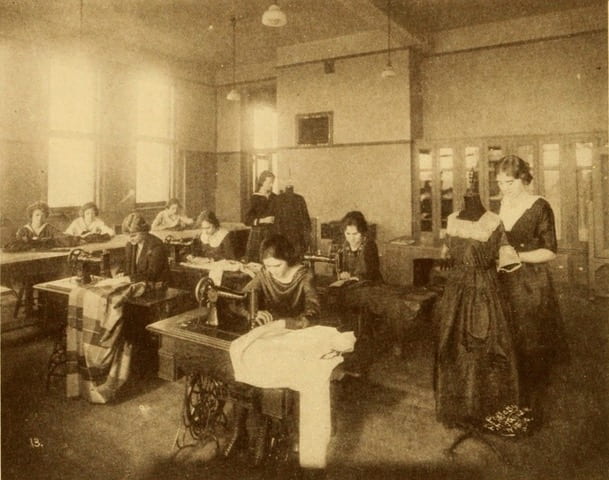

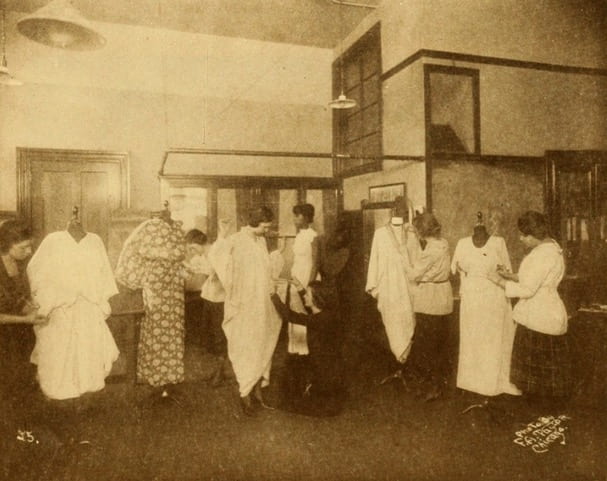

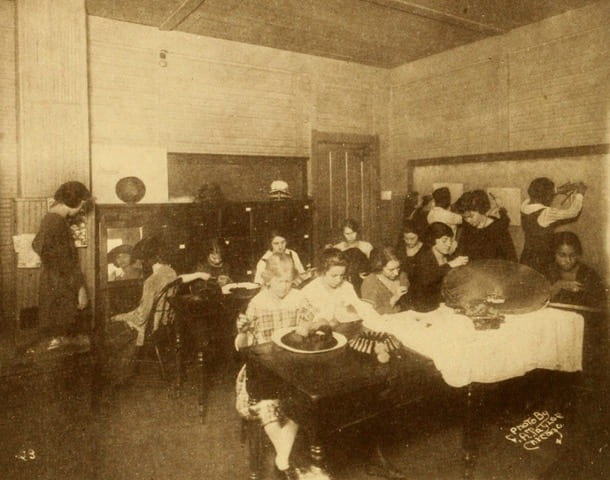

The curriculum offered at Flower Tech focused on designing, millinery, and dressmaking, and the school featured factory-style classrooms where girls could learn different techniques for working with gloves and garments. The school also had a vocational guidance counselor to help girls find jobs after at least two years of enrollment. Yet, the curriculum still emphasized “feminine social roles in the home.”

Other vocational schools for girls, such as the Hull-House Trade Schools for Girls and the Training School for Active Women Workers, offered not only dressmaking education and apprenticeship opportunities for girls over 14, but also classes focused on labor legislation and the history of the women’s movement and capitalism.

Unfortunately, the female students themselves were never really asked what they wanted to learn. The two most popular vocational programs among girls were not about homemaking; they were business-oriented: accounting and stenography (typing). Girls and young women set their sights on office work, clerical jobs, and ultimately, upward class mobility.

Dr. Oram didn’t just write an article. She successfully nominated Flower Tech for landmark status on the National Register of Historic Places in 2017. Flower Tech is among six out of 388 Chicago sites on the National Register that bears the name of a woman.