By Ánh Adams

Figure 1: Woman enters the Municipal Base Hospital used for venereal disease examinations. Source: San Antonio Municipal Base Hospital, May 1917. Courtesy of Minnie Fisher Cunningham Papers, University of Houston Libraries Special Collections.

In a photograph taken on May 31, 1917, a woman approaches the San Antonio Municipal Base Hospital to be inspected by Dr. W. A. King, a government physician whose job was to examine women for venereal disease. Depending on the results of her examination, she either left with a certificate allowing her to continue working in the vicinity of a military encampment, or she was forced into a detention home for venereally diseased women.

In the years before and during World War I, this woman’s experience was a reality for many women across the nation as the convergence of vice, disease, and military conflict, fostered fears about the threat of promiscuous women. Fear that the patriotic, self-sacrificing, boys and men serving the nation would be subject to not only the threat of venereal disease, but also the moral degeneracy of prostitutes, spread across the nation. These fears emboldened the government to create a national movement, often called the repression campaign or the American Plan, to incarcerate women and girls suspected of promiscuity on the basis that their bodies were a threat to national security.[i]

In her research “At Home, At War: Policing Women’s Sexuality in Texas,” Liberal Arts undergraduate student Ánh Adams explores the realities that women and girls faced during WWI as a result of the campaign to repress prostitution and venereal disease. Ultimately, her research contends that the federal government carried out a significant movement to regulate, control, and detain women, ultimately creating a carceral system that could prosecute a woman on the ground that her body was a threat to national security.

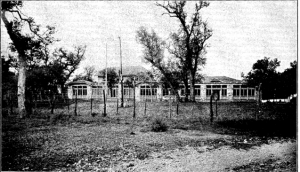

The federal campaign affected thousands of women across the nation, but was especially influential in the state of Texas, which hosted more servicemen than any other state and also had a long history of legal and illegal prostitution.[ii] The visible connections between prostitution and the military in Texas motivated the national government to dedicate millions of dollars to building detention homes for women and girls who were considered to be “promiscuous” and therefore a threat to the nation’s servicemen. This resulted in the construction of detention homes like Live Oak Farm in San Antonio (pictured below) and the Dorcas Home for Colored Girls in Houston.

Figure 2: Live Oak Farm detention home in San Antonio, TX. Source: Detention Camp for Girls with Venereal Diseases at Live Oak Farm, San Antonio, Texas, January 1919. Courtesy of Journal of Social Hygiene, Cornell University Library Digital Collections.)

During its time, the repression campaign was largely perceived as a success, ultimately detaining over 15,000 women and closing red light districts in 44 cities just in the state of Texas.[i]

However, this supposed success came at the expense of thousands of women, especially women of color, across the nation who became the enemy on the home front and victims of the war on vice and venereal disease.

The woman in white pictured above on the steps of the Municipal Base Hospital is just one example, at one point in time, of the many women who found themselves embedded in the movement to reinforce the nation’s carceral systems, forced to endure hospitalization, examination, and often, incarceration. Even after World War 1, women still found themselves subject to policing by the state, and the legacy of the repression campaign’s perceived success contributed to the expansion of detention and police systems across the nation. Even now, over a century later, the stain of the American Plan is present on the landscape, because even though the Municipal Base Hospital no longer exists on South Santa Rosa Avenue in San Antonio, the headquarters of the San Antonio Police Department now stands in its place.

[i] Dietzler and Storey, Detention Houses and Reformatories, 3-4.

[i] M.J. Exner, “Prostitution in its Relation to the Army on the Mexican Border,” Journal of Social Hygiene 3, no. 2 (April 1917): 205; Mary Macey Dietzler and T. A. Storey, Detention Houses and Reformatories as Protective Social Agencies, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1922): 23.

[ii] David C. Humphrey, “Prostitution in Texas: From the 1830s to the 1960s.” East Texas Historical Journal 33, iss. 1 (1995): 27.