Pierre Toussaint was an enslaved ma from Haiti who, in 1787, was brought to New York City, where he eventually gained his freedom and became a successful businessman and philanthropist. Pope John Paul II declared him “venerable” in 1996, which is a step toward canonization as a saint. How did Toussaint’s story of charity achieve such wide notoriety?

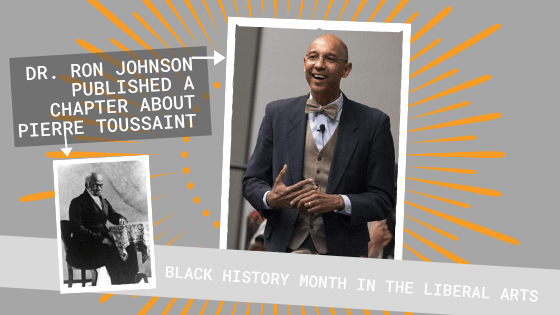

A recent chapter by Dr. Ron Johnson entitled “Enslaved by History: Slavery’s Enduring Influence on the Memory of Pierre Toussant,” published in the book Traces and Memories of Slavery in the Atlantic World, explores how myths about Toussant propelled him to fame with white Americans. “[A] white American author’s mid-nineteenth century romanticizing of slavery and silencing of the Haitian Revolution predominantly shaped the twenty-first-century memory of Pierre Toussaint.”

Johnson traces how white authors sanitized the story of Toussaint. In 1992, a New York Times article claimed that Toussaint “chose to stay, a slave” and, after being granted his freedom, he “did not abandon nor demean his enslavers.” In 1854, a White biographer of Toussaint’s life described his relationship as an enslaved man to his owners as “natural and intimate.”

Johnson argues that how white Americans remembered Toussaint had a lot to do with how they condemned the Haitian Revolution from 1791 to 1804. Lee, one white historian of the time, romanticized the “remembrance of slavery in Saint Domingue, and her repudiation of the Haitian Revolution seemed to voice support for white supremacy based upon an idealized inferiority of black people in the United States.”

Toussaint’s own papers paint a fuller picture of his legacy. Johnson describes how the papers do not support the sanitized descriptions of his life. Instead, they credit Toussaint on his own merits. “Toussaint embraced his freedom and lived a life that offered freedom and benevolence to others,” including his own sister for whom he bought freedom.

Dr. Johnson’s work shows us how historical research can help us understand important aspects of black history with more clarity and accuracy.